James Garrard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Garrard (January 14, 1749 – January 19, 1822) was an American farmer,

Following the revolution, Garrard faced the dual challenges of a growing family and depleted personal wealth. Acting on favorable reports from his former neighbor,

Following the revolution, Garrard faced the dual challenges of a growing family and depleted personal wealth. Acting on favorable reports from his former neighbor,

When Governor Isaac Shelby announced he would not seek reelection, Garrard's friends encouraged him to become a candidate. The other announced candidates were Benjamin Logan and Thomas Todd.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 33 Logan was considered the favorite in the race due to his military heroism while helping settle the Kentucky frontier. However, his oratory was unpolished, and his parliamentary skills were weak, despite his considerable political experience. Todd, who had served as secretary of all ten Kentucky statehood conventions, had the most political experience, but his youth was considered a disadvantage by some. Garrard benefited from his political connections in Bourbon County, and many held him in high regard due to his work in the Baptist church.

Under the new constitution, each of Kentucky's legislative districts chose an elector, and these electors voted to choose the governor.Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 8 Both Logan and Garrard were chosen as electors from their respective counties.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 34 On the first ballot, Logan received the votes of 21 electors, Garrard received 17, and Todd received 14.Harrison and Klotter, p. 75 A lone elector cast his vote for John Brown, a Frankfort attorney who would soon be elected to the U.S. Senate. Some speculated that Garrard's moral character prevented him from voting for himself, but his political acumen prevented him from voting for a rival, so he voted for Brown, who had not declared his candidacy. No proof exists that this was the case, however.

The constitution did not specify whether a plurality or a majority vote was required to elect the governor, but the electors, following a common practice of other states, decided to hold a second vote between Logan and Garrard in order to achieve a majority. Most of Todd's electors supported Garrard on the second vote, giving him a majority. In a letter dated May 17, 1796,

When Governor Isaac Shelby announced he would not seek reelection, Garrard's friends encouraged him to become a candidate. The other announced candidates were Benjamin Logan and Thomas Todd.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 33 Logan was considered the favorite in the race due to his military heroism while helping settle the Kentucky frontier. However, his oratory was unpolished, and his parliamentary skills were weak, despite his considerable political experience. Todd, who had served as secretary of all ten Kentucky statehood conventions, had the most political experience, but his youth was considered a disadvantage by some. Garrard benefited from his political connections in Bourbon County, and many held him in high regard due to his work in the Baptist church.

Under the new constitution, each of Kentucky's legislative districts chose an elector, and these electors voted to choose the governor.Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 8 Both Logan and Garrard were chosen as electors from their respective counties.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 34 On the first ballot, Logan received the votes of 21 electors, Garrard received 17, and Todd received 14.Harrison and Klotter, p. 75 A lone elector cast his vote for John Brown, a Frankfort attorney who would soon be elected to the U.S. Senate. Some speculated that Garrard's moral character prevented him from voting for himself, but his political acumen prevented him from voting for a rival, so he voted for Brown, who had not declared his candidacy. No proof exists that this was the case, however.

The constitution did not specify whether a plurality or a majority vote was required to elect the governor, but the electors, following a common practice of other states, decided to hold a second vote between Logan and Garrard in order to achieve a majority. Most of Todd's electors supported Garrard on the second vote, giving him a majority. In a letter dated May 17, 1796,

During Governor Shelby's term, the General Assembly had passed laws requiring that the governor, auditor,

During Governor Shelby's term, the General Assembly had passed laws requiring that the governor, auditor,

The difficulties with Garrard's election over Benjamin Logan in 1795 added to a litany of complaints about the state's first constitution. Some believed that it was undemocratic because it required electors to choose the governor and state senators and many offices were appointive rather than elective. Others opposed life terms for judges and other state officials. Still others wanted slavery excluded from the document, or to lift the ban on ministers serving in the General Assembly. In the aftermath of the disputed 1795 election, all parties involved agreed that changes were needed. The present constitution provided no means for amendment, however. The only remedy was another constitutional convention.

Calling a constitutional convention required the approval of a majority of voters in two successive elections or a

The difficulties with Garrard's election over Benjamin Logan in 1795 added to a litany of complaints about the state's first constitution. Some believed that it was undemocratic because it required electors to choose the governor and state senators and many offices were appointive rather than elective. Others opposed life terms for judges and other state officials. Still others wanted slavery excluded from the document, or to lift the ban on ministers serving in the General Assembly. In the aftermath of the disputed 1795 election, all parties involved agreed that changes were needed. The present constitution provided no means for amendment, however. The only remedy was another constitutional convention.

Calling a constitutional convention required the approval of a majority of voters in two successive elections or a

On October 16, 1802, Spanish intendent Don Juan Ventura Morales announced the revocation of the U.S. right of deposit at

On October 16, 1802, Spanish intendent Don Juan Ventura Morales announced the revocation of the U.S. right of deposit at

Biography from Lawyers and Lawmakers of Kentucky

{{DEFAULTSORT:Garrard, James 1749 births 1822 deaths American Revolutionary War prisoners of war held by Great Britain Baptist ministers from the United States Baptists from Virginia Governors of Kentucky Kentucky Democratic-Republicans Members of the Virginia House of Delegates People from Stafford County, Virginia Virginia militiamen in the American Revolution Democratic-Republican Party state governors of the United States People excommunicated by Baptist churches 18th-century American politicians 19th-century American politicians

Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

minister and politician who served as the second governor of Kentucky from 1796 to 1804. Because of term limits

A term limit is a legal restriction that limits the number of terms an officeholder may serve in a particular elected office. When term limits are found in presidential and semi-presidential systems they act as a method of curbing the potenti ...

imposed by the state constitution adopted in 1799, he was the last Kentucky governor elected to two consecutive terms until the restriction was eased by a 1992 amendment, allowing Paul E. Patton's re-election in 1999.

After serving in the Revolutionary War, Garrard moved west to the part of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

that is now Bourbon County, Kentucky

Bourbon County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 20,252. Its county seat is Paris. Bourbon County is part of the Lexington–Fayette, KY Metropolitan Statistical Area. It is one of Ken ...

. He held several local political offices and represented the area in the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-number ...

. He was chosen as a delegate to five of the ten statehood conventions that secured Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

's separation from Virginia and helped write the state's first constitution. Garrard was among the delegates who unsuccessfully tried to exclude guarantees of the continuance of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

from the document. In 1795, he sought to succeed Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic an ...

as governor. In a three-way race, Benjamin Logan

Benjamin Logan (May 1, 1743 – December 11, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia, then Shelby County, Kentucky. As colonel of the Kentucky County, Virginia militia during the American Revolutionary War, he was s ...

received a plurality, but not a majority, of the electoral votes cast. Although the state constitution did not specify whether a plurality or a majority was required, the electors held another vote between the top two candidates – Logan and Garrard – and on this vote, Garrard received a majority. Logan protested Garrard's election to state attorney general

The state attorney general in each of the 50 U.S. states, of the federal district, or of any of the territories is the chief legal advisor to the state government and the state's chief law enforcement officer. In some states, the attorney gener ...

John Breckinridge John Breckinridge or Breckenridge may refer to:

* John Breckinridge (U.S. Attorney General) (1760–1806), U.S. Senator and U.S. Attorney General

* John C. Breckinridge (1821–1875), U.S. Representative and Senator, 14th Vice President of the Unit ...

and the state senate

A state legislature in the United States is the legislative body of any of the 50 U.S. states. The formal name varies from state to state. In 27 states, the legislature is simply called the ''Legislature'' or the ''State Legislature'', whil ...

, but both claimed they had no constitutional power to intervene.

A Democratic-Republican

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

, Garrard opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed th ...

and favored passage of the Kentucky Resolutions

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued t ...

. He lobbied for public education, militia and prison reforms, business subsidies, and legislation favorable to the state's large debtor class. In 1798, the state's first governor's mansion was constructed, and Garrard became its first resident. Due in part to the confusion resulting from the 1795 election, he favored calling a constitutional convention in 1799. Because of his anti-slavery views, he was not chosen as a delegate to the convention. Under the resulting constitution, the governor was popularly elected

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are cho ...

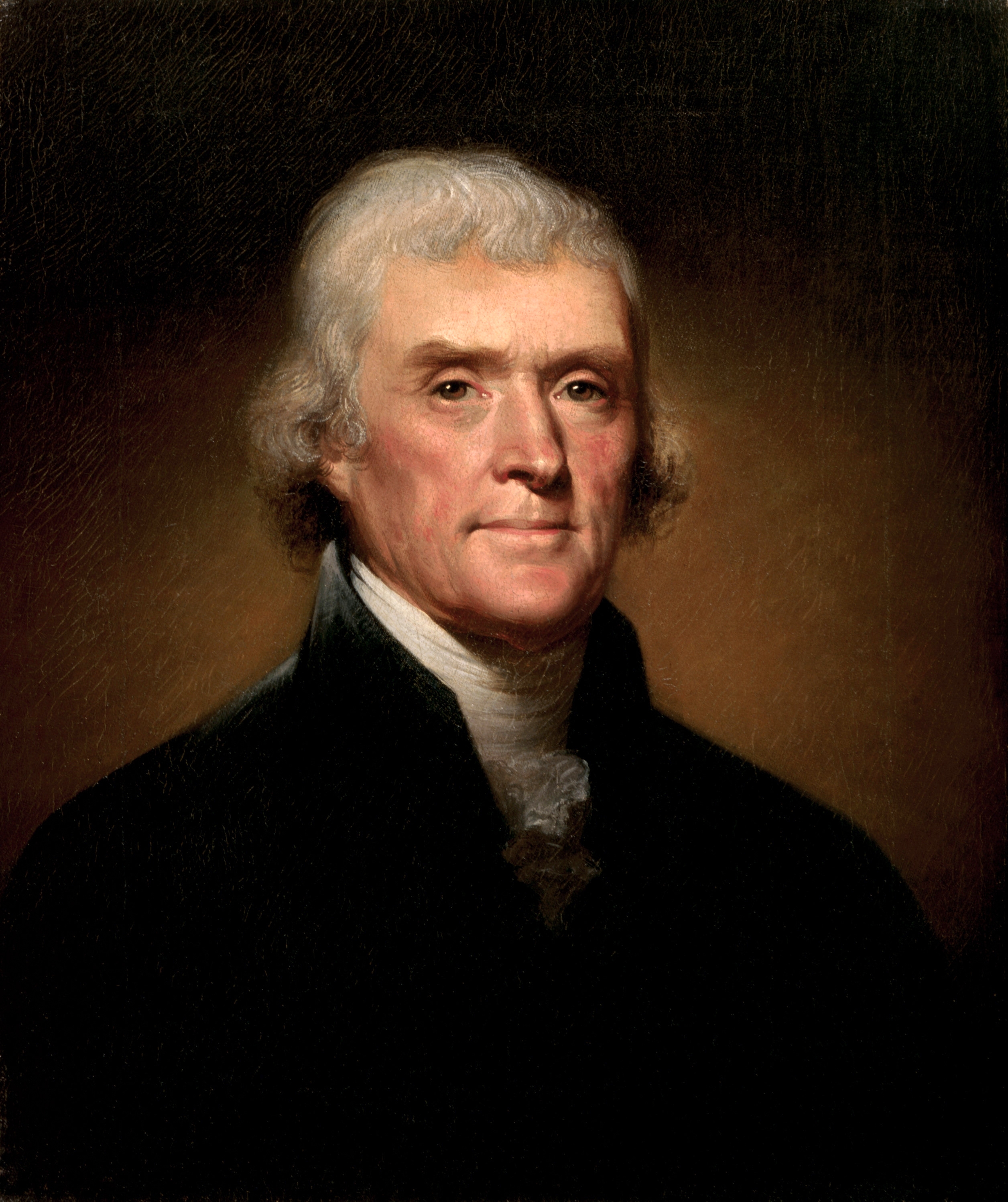

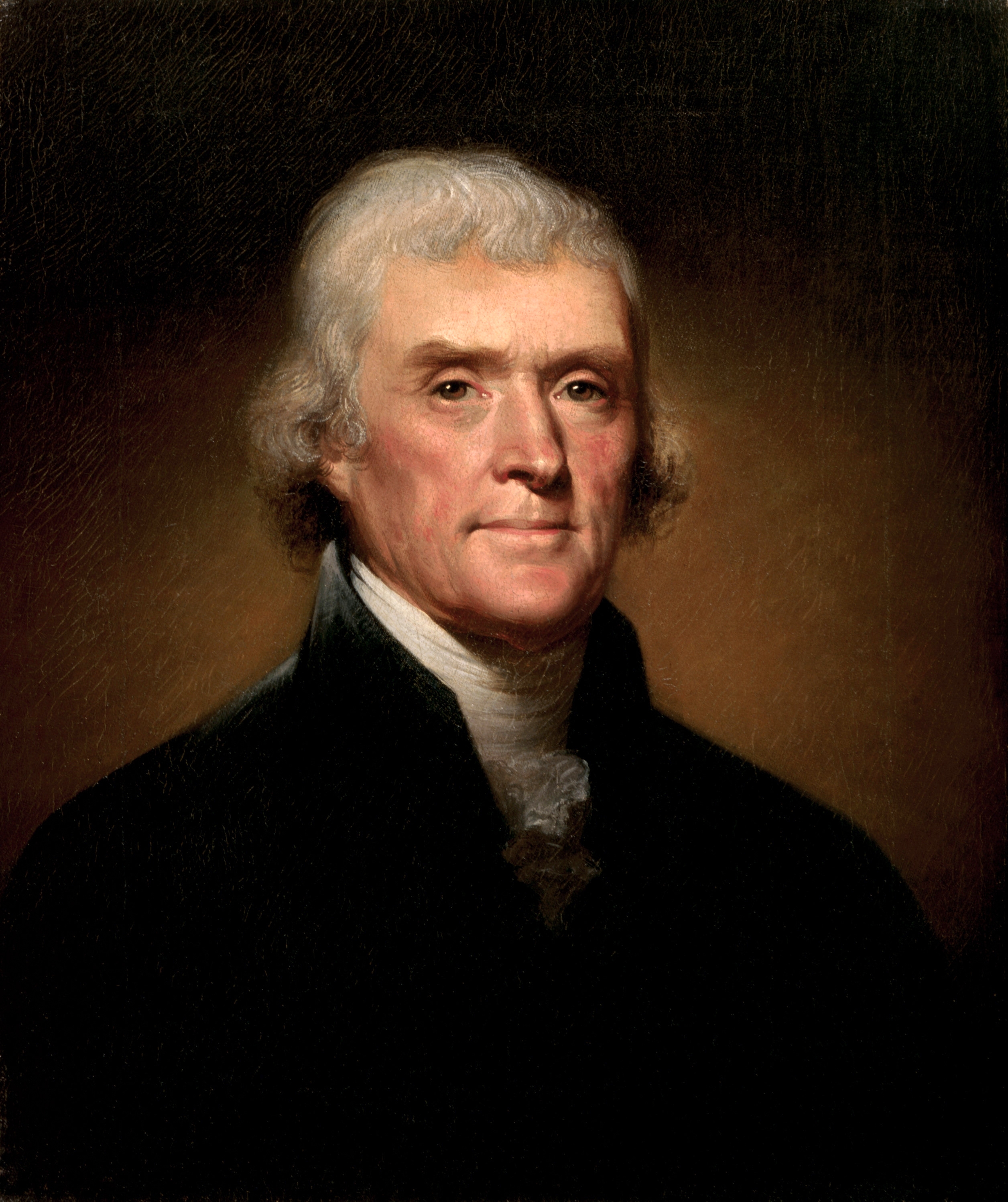

and was forbidden from succeeding himself in office, although Garrard was personally exempted from this provision and was re-elected in 1799. During his second term, he applauded Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

's purchase of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

from France as a means of dealing with the closure of the port at New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

to U.S. goods. Late in his term, his Secretary of State, Harry Toulmin, persuaded him to adopt some doctrines of Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Unitarianism

Unitarianism (from Latin ''unitas'' "unity, oneness", from ''unus'' "one") is a nontrinitarian branch of Christian theology. Most other branches of Christianity and the major Churches accept the doctrine of the Trinity which states that there i ...

, and he was expelled from the Baptist church, ending his ministry. He also clashed with the legislature over the appointment of a registrar for the state land office, leaving him embittered and unwilling to continue in politics after the conclusion of his term. He retired to his estate, Mount Lebanon, and engaged in agricultural and commercial pursuits until his death on January 19, 1822. Garrard County, Kentucky

Garrard County ( ;) is a county located in the Bluegrass Region of Kentucky. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, the county's population was 16,953. Its county seat is Lancaster. The county was formed in 1796 and was named for James Garrard, Governor ...

, created during his first term, was named in his honor.

Early life and family

James Garrard was born inStafford County, Virginia

Stafford County is located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is a suburb outside of Washington D.C. It is approximately south of D.C. It is part of the Northern Virginia region, and the D.C area. It is one of the fastest growing, and highest- ...

, on January 14, 1749.Harrison in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 363 He was second of three children born to Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

William and Mary (Naughty) Garrard.Des Cognets, p. 6 Garrard's mother died sometime between 1755 and 1760; afterward, his father married Elizabeth Moss, and the couple had four more children. William Garrard was the county lieutenant of Stafford County, by virtue of which he held the rank of colonel and was in command of the county militia. The Garrard family was moderately wealthy, and the Stafford County courthouse was built on their land.Billings and Blee, p. 58 During his childhood, James worked on his father's farm.Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 7 He was educated in the common school A common school was a public school in the United States during the 19th century. Horace Mann (1796–1859) was a strong advocate for public education and the common school. In 1837, the state of Massachusetts appointed Mann as the first secretary ...

s of Stafford County and studied at home, acquiring a fondness for books. Early in life, he associated himself with the Hartwood Baptist Church near Fredericksburg, Virginia.Des Cognets, p. 9

On December 20, 1769, Garrard married his childhood sweetheart, Elizabeth Mountjoy.Johnson, p. 721 Shortly thereafter, his sister Mary Anne married Mountjoy's brother, Colonel John Mountjoy.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 1 Garrard and his wife had five sons and seven daughters.Des Cognets, p. 15 One son and two daughters died before reaching age two. Of the surviving four sons, all participated in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

and all served in the Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in ...

.Des Cognets, p. 14 A number of his grandsons served in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, including Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

Generals Kenner Garrard

Kenner Garrard (September 21, 1827 – May 15, 1879) was a brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. A member of one of Ohio's most prominent military families, he performed well at the Battle of Gettysburg, and then le ...

and Theophilus T. Garrard

Theophilus Toulmin Garrard (June 7, 1812 – March 15, 1902) was a politician, Union general in the American Civil War, farmer, and businessman.

Early life and career

Garrard was born in Clay County, Kentucky near Manchester at the Goose C ...

. Another grandson, James H. Garrard, was elected to five consecutive terms as state treasurer, serving from 1857 until his death in 1865.

Garrard served in the Revolutionary War as a member of his father's Stafford County militia, although it is not known how much combat he participated in."James Garrard". ''Dictionary of American Biography'' While on board a schooner on the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

, he was captured by British forces. His captors offered to free him in exchange for military information, but he refused the offer and later escaped.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 2

While serving in the militia in 1779, Garrard was elected to represent Stafford County the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-number ...

, and he assumed his seat for the 1779 legislative session. His major contribution to the session was advocating for a bill that granted religious liberty to all residents of Virginia; passage of the bill ended persecution by citizens who associated with the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

upon followers of other faiths and countered an effort by some to establish the Church of England as Virginia's official church.Johnson, p. 720 After the session, he returned to his military duties. In 1781, he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

Resettlement in Kentucky

Following the revolution, Garrard faced the dual challenges of a growing family and depleted personal wealth. Acting on favorable reports from his former neighbor,

Following the revolution, Garrard faced the dual challenges of a growing family and depleted personal wealth. Acting on favorable reports from his former neighbor, John Edwards

Johnny Reid Edwards (born June 10, 1953) is an American lawyer and former politician who served as a U.S. senator from North Carolina. He was the Democratic nominee for vice president in 2004 alongside John Kerry, losing to incumbents George ...

, Garrard and Samuel Grant headed west into the recently created Kentucky County

Kentucky County (then alternately spelled Kentucke County) was formed by the Commonwealth of Virginia from the western portion (beyond the Cumberland Mountains) of Fincastle County effective December 31, 1776. The name of the county was taken ...

. By virtue of his military service, Garrard was entitled to claim any vacant land he surveyed and recorded at the state land office.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 3 Beginning in early 1783, Garrard made claims for family and friends, as well as for himself. Later in 1783, he moved his family to the land he had surveyed in Fayette County, which had been created from Kentucky County since his last visit to the region. Three years later, he employed John Metcalfe, a noted stonemason and older half-brother of future Kentucky Governor Thomas Metcalfe, to build his estate, Mount Lebanon, on the Stoner Fork of the Licking River.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 5 There, he engaged in agriculture, opened a grist mill and a lumber mill, and distilled whiskey

Whisky or whiskey is a type of distilled alcoholic beverage made from fermented grain mash. Various grains (which may be malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, corn, rye, and wheat. Whisky is typically aged in wooden ...

. In 1784, he enlisted in the Fayette County militia.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 15

In 1785, Garrard was elected to represent Fayette County in the Virginia legislature.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 4 He was placed on a legislative committee with Benjamin Logan

Benjamin Logan (May 1, 1743 – December 11, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia, then Shelby County, Kentucky. As colonel of the Kentucky County, Virginia militia during the American Revolutionary War, he was s ...

and Christopher Greenup

Christopher Greenup (c. 1750 – April 27, 1818) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative and the third Governor of Kentucky. Little is known about his early life; the first reliable records about him are documents recordin ...

to draft recommendations regarding the further division of Kentucky County. The committee recommended the creation of three new counties, including Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

, Mercer

Mercer may refer to:

Business

* Mercer (car), a defunct American automobile manufacturer (1909–1925)

* Mercer (consulting firm), a large human resources consulting firm headquartered in New York City

* Mercer (occupation), a merchant or trader, ...

, and Garrard's county of residence, Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...

. On his return from the legislature, Garrard was chosen county surveyor and justice of the peace for the newly formed county. At various times, he also served as magistrate and colonel of the county militia.

Although some historians have identified Garrard as a member of the Danville Political Club, a secret debating society that was active in Danville, Kentucky, from 1786 to 1790, his name is not found in the club's official membership records. Garrard's biographer, H. E. Everman, concludes that these historians may have mistaken Garrard's membership in the Kentucky Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge for membership in the Danville Political Club. The groups had similar aims, were active at about the same time, and had several members in common. Other notable members of the Kentucky Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge included Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic an ...

, Christopher Greenup, and Thomas Todd

Thomas Todd (January 23, 1765 – February 7, 1826) was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1807 to 1826. Raised in the Colony of Virginia, he Read law, studied law and later participated in the founding of K ...

, all future Kentucky governors or gubernatorial candidates.

Garrard's Mount Lebanon estate was designated as the temporary county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US st ...

of Bourbon County; the county court first convened there on May 15, 1786, and continued to meet there for many years. In 1789, the Virginia legislature established a permanent county seat named Hopewell, and Garrard was part of the committee chosen to survey the area for the city. He and John Edwards were among the new settlement's first trustees.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 18 Upon Garrard's recommendation, the city's name was changed to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

in 1790. Soon after, he resigned as county surveyor to focus on more pressing needs of defense for the fledgling settlement. At his behest, the Bourbon County Court expanded its militia from one battalion to two at its meeting in August 1790.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 19

Religious leadership

As early as June 25, 1785, Garrard and his friend Augustine Eastin attended meetings of the ElkhornBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

Association.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 9 In 1787, he helped organize the Cooper's Run Baptist Church near his estate. He was chosen as one of the church's elders and served the congregation there for ten years. Soon after its formation, the church joined the Elkhorn Baptist Association, and in 1789, it issued Garrard a license to preach.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 8 Although he owned as many as 23 slaves to work on his vast agricultural and industrial works, Garrard condemned slavery from the pulpit, calling it a "horrid evil". Whites and blacks participated equally in worship at Cooper's Run.

Garrard and the other elders of the church started numerous congregations in the state, including one as far away as Mason County. In 1789, Garrard and Eastin began working to reunite the more orthodox Regular Baptist

Regular Baptists are "a moderately Calvinistic Baptist sect that is found chiefly in the southern U.S., represents the original English Baptists before the division into Particular and General Baptists, and observes closed communion and foot washi ...

s in the area with the more liberal Separatist Baptists. Garrard's former church in Virginia had been a Regular Baptist congregation, and Garrard was considered a Regular Baptist despite his clear advocacy for religious toleration and his open expression of liberal views. Although he never succeeded in uniting the two factions, he was chosen moderator of the Elkhorn Baptist Association's annual meetings in 1790, 1791, and 1795 in recognition of his efforts.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', pp. 10–11

From 1785 to 1799, Garrard served as a trustee of Transylvania Seminary (now Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private university in Lexington, Kentucky. It was founded in 1780 and was the first university in Kentucky. It offers 46 major programs, as well as dual-degree engineering programs, and is accredited by the Southern ...

).Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 13 In 1794, the Baptist and more liberal trustees united against the orthodox Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

members of the board to elect the seminary's first non-Presbyterian president. That president was Harry Toulmin, a Unitarian minister from England.Billings and Blee, p. 59 Toulmin's daughter Lucinda would later marry Garrard's son Daniel.Des Cognets, p. 60 As a result of Garrard's relationship with Toulmin, he began to accept some tenets of Unitarianism, specifically the doctrines of Socinianism.Collins, p. 110 By 1802, Garrard and Augustine Eastin had not only adopted these beliefs, but had indoctrinated their Baptist congregations with them. The Elkhorn Baptist Association condemned these beliefs as heretical and encouraged Garrard and Eastin to abandon them. When that effort failed, the Association ceased correspondence and association with both men. This event ended Garrard's ministry and his association with the Baptist church.

Political career

Residents of what is now Kentucky called a series of ten conventions in Danville to arrange their separation from Virginia. Garrard was a delegate to five of these conventions, held in May and August 1785 and in 1787, 1788, and 1792.Des Cognets, p. 8 At the August 1785 convention, the delegates unanimously approved a formal request for constitutional separation.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 22 As a member of the Virginia legislature, Garrard then traveled toRichmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

for the legislative session and voted in favor of the act specifying the conditions under which Virginia would accept Kentucky's separation.

Before the final convention in 1792, a committee composed of Garrard, Ambrose Dudley, and Augustine Eastin reported to the Elkhorn Baptist Association in favor of forbidding slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the constitution then being drafted for the new state. Slavery was a major issue in the 1792 convention that finalized the document. Delegate David Rice, a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

minister, was the leading voice against the inclusion of slavery protections in the new constitution, while George Nicholas argued most strenuously in favor of them.Harrison and Klotter, p. 63 Garrard encouraged his fellow ministers and Baptists to vote against its inclusion.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 10 The motion to delete Article 9 of the proposed document, which protected the rights of slave owners, failed by a vote of 16–26. Each of the seven Christian ministers who served as delegates to the convention (including Garrard) voted in favor of deleting the article. Five Baptist laymen defied Garrard's instructions and voted to retain Article 9; their votes provided the necessary margin for its inclusion.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 11 Historian Lowell H. Harrison wrote that the anti-slavery votes of the ministers may have accounted for the adoption of a provision that forbade ministers from serving in the Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in ...

. Garrard and the other ministers apparently expressed no dissent against this provision.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 12

Aside from his opposition to slavery, Garrard did not take a particularly active role in the convention's proceedings. His most notable action not related to slavery occurred on April 13, 1792, when he reported twenty-two resolutions from the committee of the whole

A committee of the whole is a meeting of a legislative or deliberative assembly using procedural rules that are based on those of a committee, except that in this case the committee includes all members of the assembly. As with other (standing) c ...

that provided the framework for the new constitution.

Gubernatorial election of 1795

Following the constitutional convention, it appeared that Garrard's political career was drawing to a close.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 31 He resigned all of his county offices to focus on his work in the Elkhorn Baptist Convention and his agricultural pursuits.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 30 He was pleased, however, when his son William was chosen to represent the county in the state legislature in 1793. In 1795, William Garrard was reelected, and the other four state legislators from Bourbon County were close associates of Garrard's, including John Edwards, who had recently been defeated for reelection to the U.S. Senate. When Governor Isaac Shelby announced he would not seek reelection, Garrard's friends encouraged him to become a candidate. The other announced candidates were Benjamin Logan and Thomas Todd.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 33 Logan was considered the favorite in the race due to his military heroism while helping settle the Kentucky frontier. However, his oratory was unpolished, and his parliamentary skills were weak, despite his considerable political experience. Todd, who had served as secretary of all ten Kentucky statehood conventions, had the most political experience, but his youth was considered a disadvantage by some. Garrard benefited from his political connections in Bourbon County, and many held him in high regard due to his work in the Baptist church.

Under the new constitution, each of Kentucky's legislative districts chose an elector, and these electors voted to choose the governor.Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 8 Both Logan and Garrard were chosen as electors from their respective counties.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 34 On the first ballot, Logan received the votes of 21 electors, Garrard received 17, and Todd received 14.Harrison and Klotter, p. 75 A lone elector cast his vote for John Brown, a Frankfort attorney who would soon be elected to the U.S. Senate. Some speculated that Garrard's moral character prevented him from voting for himself, but his political acumen prevented him from voting for a rival, so he voted for Brown, who had not declared his candidacy. No proof exists that this was the case, however.

The constitution did not specify whether a plurality or a majority vote was required to elect the governor, but the electors, following a common practice of other states, decided to hold a second vote between Logan and Garrard in order to achieve a majority. Most of Todd's electors supported Garrard on the second vote, giving him a majority. In a letter dated May 17, 1796,

When Governor Isaac Shelby announced he would not seek reelection, Garrard's friends encouraged him to become a candidate. The other announced candidates were Benjamin Logan and Thomas Todd.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 33 Logan was considered the favorite in the race due to his military heroism while helping settle the Kentucky frontier. However, his oratory was unpolished, and his parliamentary skills were weak, despite his considerable political experience. Todd, who had served as secretary of all ten Kentucky statehood conventions, had the most political experience, but his youth was considered a disadvantage by some. Garrard benefited from his political connections in Bourbon County, and many held him in high regard due to his work in the Baptist church.

Under the new constitution, each of Kentucky's legislative districts chose an elector, and these electors voted to choose the governor.Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 8 Both Logan and Garrard were chosen as electors from their respective counties.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 34 On the first ballot, Logan received the votes of 21 electors, Garrard received 17, and Todd received 14.Harrison and Klotter, p. 75 A lone elector cast his vote for John Brown, a Frankfort attorney who would soon be elected to the U.S. Senate. Some speculated that Garrard's moral character prevented him from voting for himself, but his political acumen prevented him from voting for a rival, so he voted for Brown, who had not declared his candidacy. No proof exists that this was the case, however.

The constitution did not specify whether a plurality or a majority vote was required to elect the governor, but the electors, following a common practice of other states, decided to hold a second vote between Logan and Garrard in order to achieve a majority. Most of Todd's electors supported Garrard on the second vote, giving him a majority. In a letter dated May 17, 1796, Kentucky Secretary of State

The secretary of state of Kentucky is one of the constitutional officers of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It is now an elected office, but was an appointed office prior to 1891. The current secretary of state is Republican Michael Adams, who wa ...

James Brown certified Garrard's election, and Governor Shelby sent him a letter of congratulations on his election on May 27.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 35

Although he did not believe Garrard had personally done anything wrong, Logan formally protested the outcome of the election to Kentucky Attorney General

The Attorney General of Kentucky is an office created by the Kentucky Constitution. (Ky.Const. § 91). Under Kentucky law, they serve several roles, including the state's chief prosecutor (KRS 15.700), the state's chief law enforcement officer (K ...

John Breckinridge John Breckinridge or Breckenridge may refer to:

* John Breckinridge (U.S. Attorney General) (1760–1806), U.S. Senator and U.S. Attorney General

* John C. Breckinridge (1821–1875), U.S. Representative and Senator, 14th Vice President of the Unit ...

. Breckinridge refused to render an official decision on the matter, claiming that neither the constitution nor the laws of the state empowered him to do so. Privately, however, he expressed his opinion that Logan had been legally elected. Logan then appealed to the state senate

A state legislature in the United States is the legislative body of any of the 50 U.S. states. The formal name varies from state to state. In 27 states, the legislature is simply called the ''Legislature'' or the ''State Legislature'', whil ...

, which was given the authority to intervene in disputed elections. In November 1796, the Senate opined that the law giving them that authority was unconstitutional because it did not promote the "peace and welfare" of the state. State senator Green Clay

Green Clay (August 14, 1757 – October 31, 1828) was an American businessman, planter, military officer and politician from Kentucky. Clay served in the American Revolutionary War and was commissioned as a general to lead the Kentucky militia ...

was the primary proponent of this line of reasoning.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 36 By this time, Garrard had been serving as governor for five months, and Logan abandoned the quest to unseat him.

First term as governor

Garrard was regarded as a strong chief executive who surrounded himself with knowledgeable advisors. His friend, John Edwards, and his son, William Garrard, were both in the state senate and kept him abreast of issues there.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 39 He showed that he was willing to continue with Shelby's direction for the state by re-appointing Secretary of State James Brown, but the aging Brown retired in October 1796, only a few months into Garrard's term. Garrard then appointed Harry Toulmin, who had resigned the presidency of Transylvania Seminary in April due to opposition from the institution's more conservative trustees. Although he did not retain outgoing Attorney General John Breckinridge, who had sided with Logan in the disputed gubernatorial election, Garrard still frequently consulted with him on complex legal questions. During Governor Shelby's term, the General Assembly had passed laws requiring that the governor, auditor,

During Governor Shelby's term, the General Assembly had passed laws requiring that the governor, auditor, treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

, and secretary of state live in Frankfort and allocating a sum of 100 pounds to rent living quarters for the governor.Clark and Lane, p. 5 Shortly after Garrard took office, the state commissioners of public buildings reported to the legislature that it would be more financially sensible to construct a house for the governor and his large family than to rent living quarters for them for the duration of his term.Clark and Lane, p. 6 On December 4, 1796, the General Assembly passed legislation appropriating 1,200 pounds for the construction of such a house. The state's first governor's mansion was completed in 1798. Garrard incited considerable public interest when, in 1799, he commissioned a local craftsman to build a piano for one of his daughters; most Kentuckians had never seen such a grand instrument, and a considerable number of them flocked to the governor's mansion to see it when it was finished.Clark and Lane, p. 10 Kentucky historian Thomas D. Clark

Thomas Dionysius Clark (July 14, 1903 – June 28, 2005) was an American historian. Clark saved from destruction a large portion of Kentucky's printed history, which later became a core body of documents in the Kentucky Department for Libraries and ...

also relates that Garrard's addition of carpeting to the mansion – a rare amenity at the time – drew many visitors and was described by one as "the envy and pride of the community".Clark and Lane, p. 11

Among the other acts passed during the first year of Garrard's term were laws establishing the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

Th ...

and a system of lower district courts.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 44 For the first time, lawyers in the state were required to be licensed. Six new counties – including one named in Garrard's honor – were created, along with several new settlements. Garrard approved enabling acts creating twenty-six counties; no other Kentucky governor oversaw the creation of as many.

Left undone, however, was extending the laws dealing with surveying and registering land claims with the registrar of the state land office.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 48 Cognizant that the old law would expire November 30, 1797, Garrard issued a proclamation on November 3 calling the legislature into special session. The legislators convened on November 28, and Garrard, drawing on his experience as a surveyor, addressed them regarding the urgency of adopting a new law and forestalling more lawsuits related to land claims, which were already numerous. Although a wealthy landowner himself, Garrard advocated protecting Kentucky's large debtor class from foreclosure on their lands. Garrard supported pro- squatting legislation, including measures that forbade the collection of taxes from squatters on profits they made from working the land they occupied and that required landowners to pay squatters for any improvements they made on their land. Despite opposition from some aristocratic legislators like John Breckinridge, most of the reforms advocated by Garrard were approved in the session.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 50

Garrard was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

and agreed with party founder Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

's condemnation of the Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed th ...

. In an address to the General Assembly on November 7, 1798, he denounced the Alien Act on the grounds that it deterred desirable immigration; the Sedition Act, he claimed, denied those accused under its provisions freedom of speech and trial by jury

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are used in a significan ...

, rights – he pointed out – that he and the other soldiers of the Revolutionary War had fought to secure.Harrison and Klotter, p. 82Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 10 He advocated the nullification

Nullification may refer to:

* Nullification (U.S. Constitution), a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify any federal law deemed unconstitutional with respect to the United States Constitution

* Nullification Crisis, the 1832 confront ...

of both laws, but also encouraged the legislature to reaffirm its loyalty to the federal government and the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. He was supportive of the Kentucky Resolutions

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued t ...

of 1798 and 1799.

Among the other issues addressed in the 1798 General Assembly was the adoption of penal reforms. Garrard was supportive of the reforms – which included the abolition of the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

for all crimes except murder – and lobbied for the education of incarcerated individuals.Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 9Harrison and Klotter, p. 83 He also secured the passage of laws reforming and expanding the militia. Among the reforms were the imposition of penalties upon "distractors" in the militia, provisions for citizens' hiring of substitutes to serve in the militia on their behalf, and the exemption of jailers, tutors, printers, judges, ministers, and legislative leaders from service. Garrard opposed lowering taxes, instead advocating increased spending on education and business subsidies. To that end, he signed legislation combining Transylvania Seminary and Kentucky Academy into a single institution.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 57

A new constitution

The difficulties with Garrard's election over Benjamin Logan in 1795 added to a litany of complaints about the state's first constitution. Some believed that it was undemocratic because it required electors to choose the governor and state senators and many offices were appointive rather than elective. Others opposed life terms for judges and other state officials. Still others wanted slavery excluded from the document, or to lift the ban on ministers serving in the General Assembly. In the aftermath of the disputed 1795 election, all parties involved agreed that changes were needed. The present constitution provided no means for amendment, however. The only remedy was another constitutional convention.

Calling a constitutional convention required the approval of a majority of voters in two successive elections or a

The difficulties with Garrard's election over Benjamin Logan in 1795 added to a litany of complaints about the state's first constitution. Some believed that it was undemocratic because it required electors to choose the governor and state senators and many offices were appointive rather than elective. Others opposed life terms for judges and other state officials. Still others wanted slavery excluded from the document, or to lift the ban on ministers serving in the General Assembly. In the aftermath of the disputed 1795 election, all parties involved agreed that changes were needed. The present constitution provided no means for amendment, however. The only remedy was another constitutional convention.

Calling a constitutional convention required the approval of a majority of voters in two successive elections or a two-thirds majority 2/3 may refer to:

* A fraction with decimal value 0.6666...

* A way to write the expression "2 ÷ 3" ("two divided by three")

* 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines of the United States Marine Corps

* February 3

* March 2

Events Pre-1600

* 537 – ...

of both houses of the General Assembly.Harrison and Klotter, p. 76 In February 1797, the General Assembly voted to put the question before the electorate in the upcoming May elections. Of the 9,814 votes cast, 5,446 favored the call and 440 opposed it, but 3,928 had not voted at all, and several counties recorded no votes on the issue either way. This cast doubt in the minds of many legislators regarding the true will of the people. Opponents of the convention claimed that the abstentions should be counted as votes against the call; this position had some merit, as it was well known that many Fayette County voters had abstained as a protest against the convention.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 47 When all of the irregularities were accounted for, the General Assembly determined that the vote had fallen short of the required majority.

On February 10, 1798, Garrard's son William, still serving in the state senate, introduced a bill to hold another vote on calling a constitutional convention.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 51 In May 1798, 9,188 of the 16,388 votes were in favor of calling a convention. Again, almost 5,000 of the ballots contained no vote either way. On November 21, 1798, the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

voted 36–15 in favor of a convention, and the Senate provided its requisite two-thirds majority days later. No official tally of the Senate's vote was published.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 58 The Assembly's vote rendered moot any doubts about the popular vote.

Delegates to the July 22, 1799, convention were elected in May 1799. Neither Garrard nor his son William were chosen as delegates, mostly due to their anti-slavery views. Garrard had been a more active governor than his predecessor, frequently employing his veto and clashing with the county courts. As a result, the delegates moved to reign in some of the power given to the state's chief executive. Under the 1799 constitution, the governor was popularly elected

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are cho ...

, and the threshold for overriding a gubernatorial veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

was lowered from a two-thirds majority of each house of the legislature to an absolute majority.Harrison and Klotter, p. 78 Although the governor retained broad appointment powers, the state senate was given the power to approve or reject all gubernatorial nominees.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 59 New term limits

A term limit is a legal restriction that limits the number of terms an officeholder may serve in a particular elected office. When term limits are found in presidential and semi-presidential systems they act as a method of curbing the potenti ...

were imposed on the governor, making him ineligible for reelection for seven years following the expiration of his term. The restriction on ministers serving in the legislature was retained and extended to the governor's office. Historian Lowell Harrison held that this restriction was "a clear snub to Garrard", but Garrard biographer H. E. Everman maintained that it was "definitely not a blow aimed at Garrard". Garrard was personally exempted from both the succession and ministerial restrictions, clearing the way for him to seek a second term.

1799 gubernatorial election

Confident that the results of the 1795 election would be reversed, Benjamin Logan was the first to declare his candidacy for the governorship in 1799. Garrard and Thomas Todd declared their respective candidacies soon after. FormerU.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

Christopher Greenup

Christopher Greenup (c. 1750 – April 27, 1818) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative and the third Governor of Kentucky. Little is known about his early life; the first reliable records about him are documents recordin ...

also sought the office. Many of the recent settlers in Kentucky were unaware of his illustrious military record and unimpressed with his unsophisticated speaking skills.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 63 Although the candidates themselves rarely spoke negatively of each other, opponents of each candidate independently raised issues that they felt would hurt that candidate. John Breckinridge, Garrard's long-time political nemesis, tried to goad Garrard into making another impassioned plea for emancipation of slaves, which was a minority position in the state, but Garrard recognized Breckinridge's tactics and refused to express any bold emancipationist sentiments during the campaign. The fact that the slavery protections in the new constitution were even stronger than those in the previous document ensured that the incumbent's previous anti-slavery sentiments were not a major concern to most of the electorate. The family of Henry Field, a prominent leader in Frankfort, attacked Garrard for not issuing a pardon for Field, who was convicted of murdering his wife with an ax. After examining the evidence in the case, Garrard concluded that the verdict was reached justly and without undue outside influence, but the charge was raised so late in the campaign that Garrard's defense of his refusal to issue a pardon could not be circulated widely.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 64

With the advantages of incumbency and a generally popular record, Garrard garnered large majorities in the state's western counties, Jefferson County, and the Bluegrass region

The Bluegrass region is a geographic region in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It makes up the central and northern part of the state, roughly bounded by the cities of Frankfort, Paris, Richmond and Stanford. The Bluegrass region is characteriz ...

of central Kentucky. Surprisingly, he even found support among some voters who had favored Logan four years earlier. The final voting showed Garrard the winner with 8,390 votes, followed by Greenup with 6,746, Logan with 3,996, and Todd with 2,166. Due to the term limits imposed by the new constitution, Garrard was the last Kentucky governor elected to succeed himself until a 1992 amendment to the state constitution loosened the prohibition on gubernatorial succession, and Paul E. Patton was reelected in 1999.Blanchard, p. 251 In 1801, Garrard nominated Todd to fill the next vacancy on the Kentucky Court of Appeals after the election.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 65 Similarly, he appointed Greenup to a position on the Frankfort Circuit Court in 1802.

Second term as governor

The first two years of Garrard's second term were relatively uneventful, but in the 1802 General Assembly, legislators approved two bills related to the circuit court system that Garrard vetoed. The first bill expanded the number of courts and provided that untrained citizens could sit as judges in the court system. Garrard questioned the cost of the additional courts and the wisdom of allowing untrained judges on the bench; he also objected to the bill's circumvention of the governor's authority to appoint judges. The second bill allowed attorneys and judges in the circuit court system to reside outside the districts they served. The General Assembly overrode Garrard's second veto, marking the first time in Kentucky history that a gubernatorial veto was overridden and the only time during Garrard's eight-year tenure. On October 16, 1802, Spanish intendent Don Juan Ventura Morales announced the revocation of the U.S. right of deposit at

On October 16, 1802, Spanish intendent Don Juan Ventura Morales announced the revocation of the U.S. right of deposit at New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, a right that had been guaranteed under Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795 by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

.Harrison and Klotter, p. 84 The closure of the port to U.S. goods represented a major impediment to Garrard's hopes of establishing a vibrant trade between Kentucky and the other states and territories along the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. He urged President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

to act and publicly declared that Kentucky had 26,000 militiamen ready to take New Orleans by force if necessary.Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 11 Jefferson was unaware, however, that the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso had ceded control of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

to the French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in 1800, although a formal transfer had not yet been made. As Jefferson deliberated, Napoleon unexpectedly offered to sell Louisiana to the United States for approximately $15 million. Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

and James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

, Jefferson's envoys in France, accepted the offer. The purchase delighted most Kentuckians, and Garrard hailed it as a "noble achievement". Soon after the agreement, the Spanish government claimed that the French had not performed their part of the Treaty of Ildefonso and, as a result, the treaty was nullified and Louisiana still belonged to Spain. Jefferson ignored the Spanish protest and prepared to take Louisiana by force. He instructed Garrard to have 4,000 militiamen ready to march to New Orleans by December 20, 1803. The Kentucky General Assembly quickly passed a measure guaranteeing 150 acres of land to anyone who volunteered for military service, and Garrard was soon able to inform Jefferson that his quota was met. Spain then reversed course, relinquishing its claims to Louisiana, and the territory passed into U.S. control two months later.

The last months of Garrard's second term were marred by a dispute with the General Assembly over naming a new registrar of the state's land office.Everman in ''Kentucky's Governors'', p. 12 Garrard first named Secretary of State Harry Toulmin, but the Senate rejected that nomination on December 7, 1803.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 77 Next, Garrard nominated former rival Christopher Greenup, but Greenup had designs on succeeding Garrard and asked Garrard to withdraw the nomination, which he did.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 76 The Senate then rejected Garrard's next nominee, John Coburn, and accused the next, Thomas Jones, of "high criminal offense" and barred him from any further appointive office.

Following Jones' rejection, Garrard vetoed a bill that would have allowed the legislature to select the state's presidential and vice-presidential electors; despite the fact that the law ran contrary to the state constitution, Garrard's veto further strained his relations with the Senate. After the Senate rejected nominee William Trigg, the state's newspapers openly talked of an executive-legislative feud and claimed the Senate had its own favorite candidate for the position and would not accept anyone else.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 78 When the Senate rejected Willis Green

Willis Green (1818–1893) Green was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky

Life

Willis Green, son of Stephen Green and Elizabeth Stuart Green, was born in Madison County, Kentucky about 1818. Willis owned a mill at the Falls of Rough. He served a ...

in January 1804, Garrard declared that he would make no more nominations for the position. Accusations of bad faith were exchanged between the governor and the Senate, after which Garrard nominated John Adair

John Adair (January 9, 1757 – May 19, 1840) was an American pioneer, slave trader, soldier, and politician. He was the eighth Governor of Kentucky and represented the state in both the U.S. House and Senate. A native of South Carolina, Ada ...

, the popular Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

. The Senate finally confirmed this choice.

Later life and death

His dispute with the General Assembly over the naming of a land registrar left Garrard embittered, and he retired from politics at the expiration of his second term. He privately backed Christopher Greenup's bid to succeed him in 1804, and Bourbon County's vote broke heavily for Greenup in the election.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 79 Although his sons William and James would continue running for public office into the 1830s, Garrard never indicated a desire to run again.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 81 Garrard returned to Mount Lebanon, where he developed a reputation as a notable agriculturist. His son James oversaw the day-to-day operation of the farm and frequently won prizes for his innovations at local agricultural fairs.Everman in ''Governor James Garrard'', p. 80 The Mount Lebanon estate was badly damaged by one of theNew Madrid earthquakes

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

in 1811, but Garrard insisted on repairing the damage as thoroughly as possible in order to reside there for the rest of his life. He imported fine livestock – including thoroughbred

The Thoroughbred is a horse breed best known for its use in horse racing. Although the word ''thoroughbred'' is sometimes used to refer to any breed of purebred horse, it technically refers only to the Thoroughbred breed. Thoroughbreds are c ...

horses and cattle – to his farm and invested in several commercial enterprises, including several saltworks, which passed to his sons upon his death. He died on January 19, 1822, following several years of feeble health.Des Cognets, p. 13 He was buried on the grounds of his Mount Lebanon estate, and the state of Kentucky erected a monument over his grave site.

Notes

*In her research of the Garrard family, Anna Russell Des Cognets notes that thirteen years elapsed between the birth of Garrard's older brother Daniel and James Garrard. She speculates that other children, who died in infancy, may have been born to Garrard's parents during this period, but notes that she is unable to locate any records confirming this. (Des Cognets, p. 6)References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

Biography from Lawyers and Lawmakers of Kentucky

{{DEFAULTSORT:Garrard, James 1749 births 1822 deaths American Revolutionary War prisoners of war held by Great Britain Baptist ministers from the United States Baptists from Virginia Governors of Kentucky Kentucky Democratic-Republicans Members of the Virginia House of Delegates People from Stafford County, Virginia Virginia militiamen in the American Revolution Democratic-Republican Party state governors of the United States People excommunicated by Baptist churches 18th-century American politicians 19th-century American politicians